Are Gig Jobs Transforming the Labor Markets?

By Patrick J. Flaherty, Assistant Director of Research, DOL

any believe that the economy and particularly the labor markets are being transformed because of the ability to order everything from a ride to a home repair via a smartphone app. Headlines such as “The gig economy workforce will double in four years” 1 and academic papers with titles such as “The Rise and Nature of Alternative Work Arrangements in the United States” 2 have promoted this idea. Others have raised doubts. A recent New York Times story 3 stated, “You can see the gig economy everywhere but in the statistics” while the Conference Board recently issued a report titled “Contrary to the Hype – Real Trends in Nontraditional Work” 4 which stated “in 2017, the share of nontraditional workers was no different than it was 20 years ago.” The data do not show a clear picture.

any believe that the economy and particularly the labor markets are being transformed because of the ability to order everything from a ride to a home repair via a smartphone app. Headlines such as “The gig economy workforce will double in four years” 1 and academic papers with titles such as “The Rise and Nature of Alternative Work Arrangements in the United States” 2 have promoted this idea. Others have raised doubts. A recent New York Times story 3 stated, “You can see the gig economy everywhere but in the statistics” while the Conference Board recently issued a report titled “Contrary to the Hype – Real Trends in Nontraditional Work” 4 which stated “in 2017, the share of nontraditional workers was no different than it was 20 years ago.” The data do not show a clear picture.

UNITED STATES

A great deal of information is collected and published about traditional payroll employment. The monthly survey of payroll employment is benchmarked each year to the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) which gives detailed information about employment and earnings for all jobs covered by unemployment insurance (UI). To understand other types of employment (such as self-employment and independent contractors) we look to surveys such as the Current Population Survey (CPS) conducted for the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics or the American Community Survey (ACS) of the U.S. Census. Tax data have also been used to try to understand alternative work arrangements. Whether or not work arrangements appear to be undergoing large-scale changes depends in part on the source of the data being studied and the specific question being asked.

The broad surveys of the labor force show no evidence for the rise in the “Gig” economy. The CPS is conducted each month and is used to calculate the monthly unemployment rate. Each adult member of the surveyed household is classified as either employed, unemployed, or not in the labor force. Employed household members are classified as either a wage and salary worker or self-employed. The portion of workers who self-identify as self-employed has not changed over the past 20 years, an apparent contradiction to the touted rise of the “Gig Economy.” The Contingent Worker Supplement – a set of additional questions asked to CPS respondents in May 2017 – showed a decrease in contingent and alternative work arrangements from February 2005, the most recent time the survey was conducted. These results are consistent with the American Community Survey which has shown a decline in self-employment rates.

Other surveys show that there has been an increase in the number of people who have some earnings outside of traditional wage and salary employment. The Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2017 published by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System shows that three in ten adults work in the gig economy, though generally as a supplemental source of income. Similarly, economists from the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston found that as of 2015 “roughly 37% of non-retired U.S. adults participated in some type of informal work.” And of course there is no denying the growth in ride-sharing services. The Nonemployer Statistics of the U.S. Census shows an explosive increase in the number of “nonemployers” (mostly self-employed individuals) in the “taxi and limousine services” industry. The number took nearly 15 years to double from 100,000 to 200,000 in 2012 and then grew to over 700,000 by 2016 including a 45.9% increase in 2016 alone.

The Detailed Earnings Record (DER) of the IRS shows an increase in the number of self-employed. A study matching the DER to those who responded to the CPS showed a large number who reported self-employment income to the IRS who were not classified as self-employed in the CPS, including a significant number who were classified as “Not in the Labor Force”. 5 The number with self-employment income in the DER who were not self-employed in the CPS has also been rising.

There are several possible explanations for the apparent contradictions in the data. One is that the broad surveys (CPS and ACS) tend to focus on a respondent’s “main job” and may not do a good job of collecting information about work activities respondents consider supplemental. The number of “gig” workers may be rising, but those workers who hold traditional payroll jobs as well are only reporting those jobs to the CPS and ACS. The agencies conducting these surveys are considering improving the questions to more accurately capture data on alternative work arrangements. And while the growth rate for ride-sharing services has been rapid, even at 700,000 this is less one-half of one percent of the level of overall payroll employment. No other industry has similar numbers. The mixed messages from the data mean it is too early to tell whether the growth in ride-sharing is a harbinger of future transformations or a unique case.

CONNECTICUT

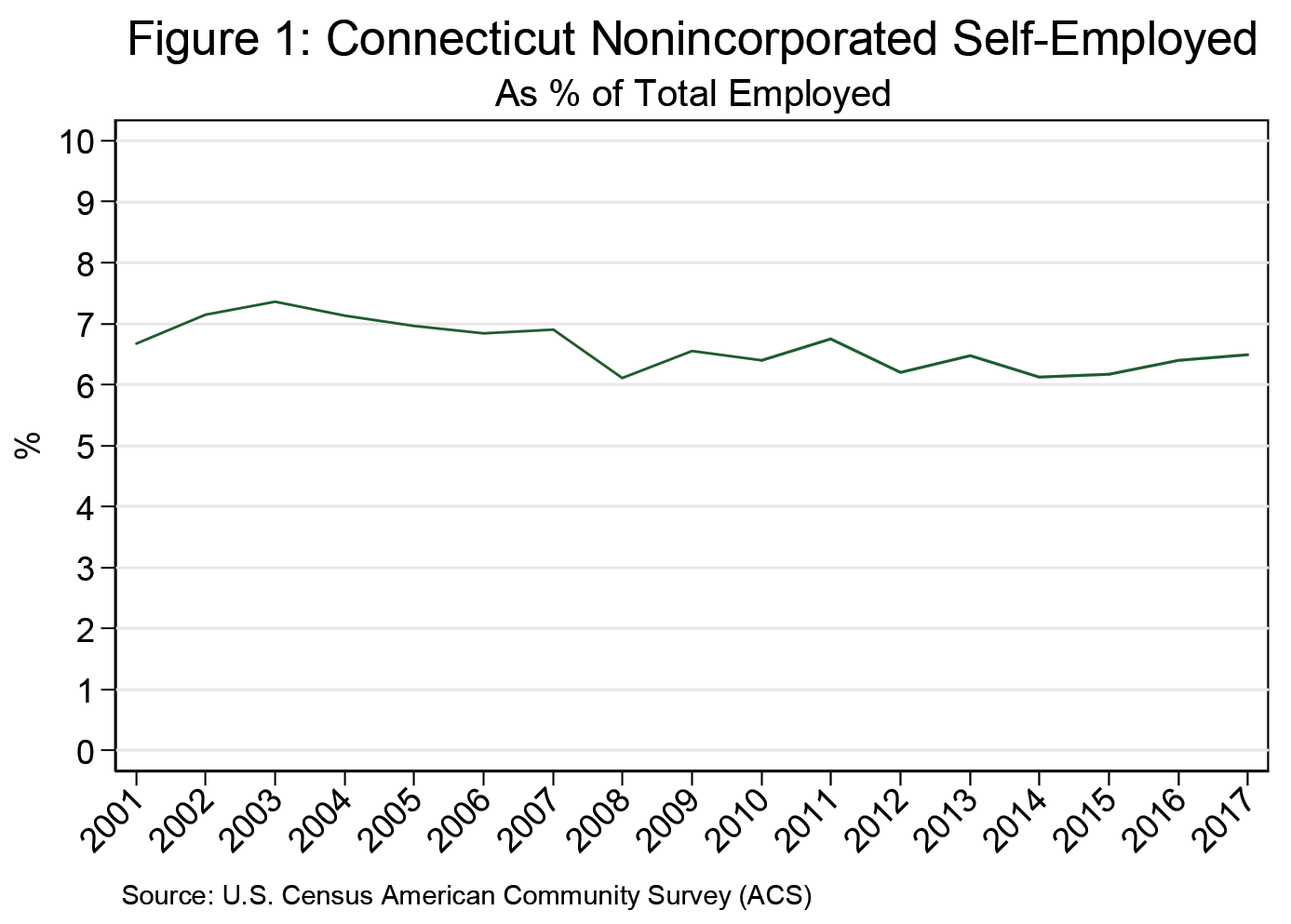

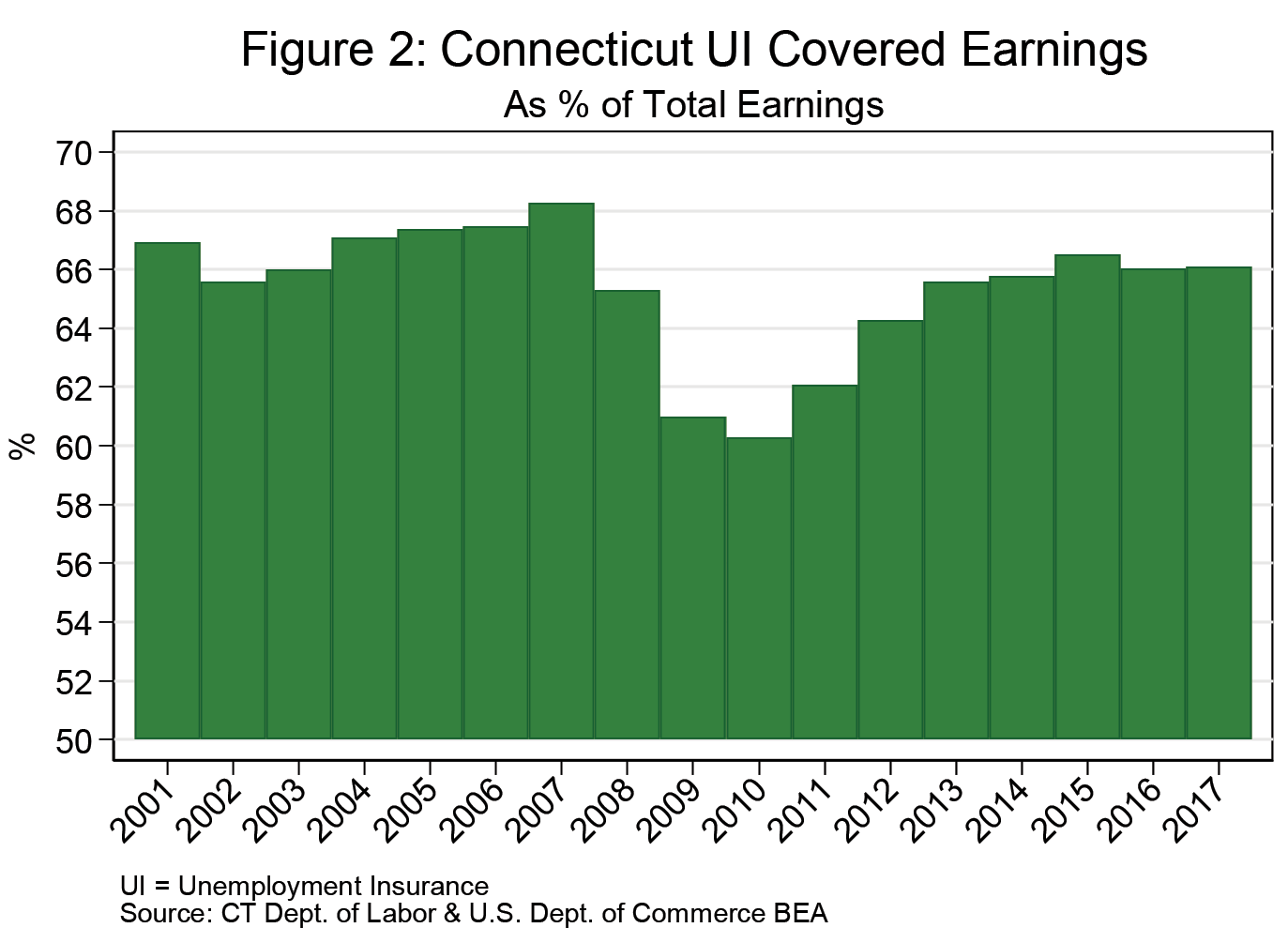

Consistent with the national data, Connecticut’s broad indicators show no rise in “Gig” employment. As of October 2018, the level of payroll employment in the Current Employment Statistics (CES) was at 93% of the number employed in the Local Area Unemployment Statistics (LAUS). 6 By design, the two surveys don’t measure exactly the same thing, but a large increase in “gig” jobs replacing traditional payroll jobs could cause the series to diverge in a way that is not currently apparent. Similarly, the American Community Survey shows less than 7% of those employed being self-employed in non-incorporated businesses with no upward trend (and perhaps a slight downward trend) over the past fifteen years (Figure 1). Finally, traditional payroll jobs remain the largest source of earnings in the economy. Comparing total wages (covered earnings) from the QCEW to total earnings by place of work from the personal income statistics shows that covered wages fell as a portion of total earnings during the great recession – perhaps as workers who lost their payroll jobs took “gig work” to provide income during that difficult time. However, covered wages are back to 66% of total earnings – the same as in the early 2000s and just two percentage points below their peak before the start of the great recession (Figure 2).

CONCLUSION

Smartphone apps and other technological innovations have changed the way we order rides and take-out meals and have provided innovative ways to earn income. Whether this has led to a rise in the number of people whose primary income is from nontraditional work is a question for further research. Unfortunately there is no clear answer because, by its nature, “gig” or “on demand” work is not documented as well as traditional jobs. Even if there is a rise in non-traditional work, a further question is how much of this is voluntary and how many “gig” workers would prefer to have traditional payroll jobs. This is an area that warrants further research. On one hand, the number of Connecticut workers who report they are working part-time but would rather work full-time is higher than it was before the 2007-2010 great recession (although down significantly from 2010). On the other hand, the record number of job openings reported nationally – and the evidence of a large number of job postings in Connecticut discussed on page 4 – suggest there are many opportunities for workers who prefer a traditional payroll job.

To further this research, Connecticut has joined with other states and the National Governors Association in a multi-state collaborative project that supports efforts to analyze and understand the on-demand economy and its implications for workers and economic growth.

1 Rani Molla, Recode.net, May 25, 2017.

2 Laurence F. Katz & Alan B. Krueger, NBER Working Paper 22667, September 2016.

3 Ben Cassleman, “Maybe the Gig Economy Isn’t Reshaping Work After All,” June 7, 2018.

4 Gad Levanon, Elizabeth Crofoot, and Brian Schaitkin, Research Report 1673-18, 2018.

5 Katharine Abraham, John Haltiwanger, Kristin Sandusky, and James Spletzer, “Measuring the Gig Economy: Current Knowledge and Open Issues,” NBER Working Paper 24950, August 2018.

6 The LAUS figures are calculated from with CPS (and other indicators) and measure the number of Connecticut residents who are employed, whether in payroll jobs or self-employed. LAUS employment also includes Connecticut residents who are employed in other states. CES is a count of jobs and includes residents of other states who are working in payroll jobs in Connecticut (and not Connecticut residents who work elsewhere). Because it is a count of jobs, workers with more than one payroll job will count more than once.